Kassandra

Police lights illuminate the half-acre farm, flickers of red and blue thrown against the chain-link fence, against the cluster of pines. The animals are absent. I’m on the wrong side of the fence, standing where the three new lambs graze during the day. My sister is on one side of me, a girl I went to high school with on the other. There is someone else on the field with us. Their back to South Street, they grip a gun in one hand. With the police lights behind them I can’t make out specifics. They’re a void in the night, something the scant light hits the wrong side of. Though they are drawing closer I can’t discern their features. Somewhere behind me on the field, maybe wilted against the side of the chicken coop, is my mother. She is dead. If she isn’t, I am certain she will be soon, a certainty like an oncoming avalanche. In front of me the gun wavers, twitches towards my sister. Someone is holding me by the arms, keeping me from darting forward. There is a stillness in me, a chill I didn’t think any person could withstand.

Only when the bullet hits my sister can I move. I don’t remember where she was shot. Not the head, nowhere that would immediately kill her. I remember this because there is time for me to hold her, her body going limp and her head in my lap. The police lights continue to pulse. She is dying and I explain that I will die soon, too, even if the gunman doesn’t shoot me. I will die soon because I’ll take the gun and do it myself if I have to because my sister is dying and my mother is dead or is going to be soon enough.

~

In other dreams, my mother becomes cruel. In one, I stumble towards her clutching a stab wound in my abdomen. She scowls and tells me to lie down, as though my blood, the evidence of my fragile humanity, disgusts her. If this mother smoked, she would be flicking the ash towards me. When I lie down and don’t die, she hoists me up and tells me we’ll walk home. I ask for a hospital or at least some bandages, trying to push my blood back into my body with an open palm. She tells me to hurry up.

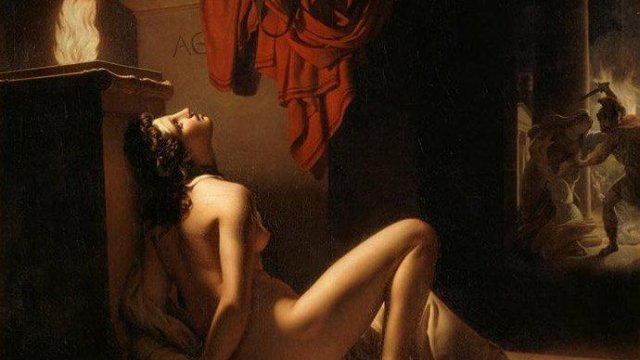

In another, we are all in mortal danger. I don’t remember what threatens us. Maybe it is a murderer, maybe a poltergeist, maybe the nuclear power plant down the road is finally giving out. I am tugging my mother’s arm, my face slick with tears, my breath high and thready, mangled by sobs. “We have to go,” I insist. “We’re going to die if we don’t.” The certainty is heavy and terrible. I understand why paintings show Kassandra tearing the hair from her own scalp.

“Calm down, Jane,” she tells me without making eye contact, scowling at her fingernails. “You’re being hysterical.” No matter what I do, no matter how hard I plead and cry and bleed, the mother in my dreams will not listen to me.

~

In the mornings I come downstairs to her hunched over a jigsaw puzzle. While I wait for my tea to steep, she tells me her plans for the day and I tell her mine. When she stands to wash her dishes, I extend my arms and smile when she hugs me, the texture of her bathrobe a familiar comfort against my cheek. Breathing against her in the quiet kitchen, I reaffirm my understanding of my mother, the version of her from my nightmares retreating with each second we hold each other, with my offer to take the dog out and her offer to make me french toast.

The dream-mother retreats, but she does not vanish. I can’t dispel her entirely because I don’t understand her. Something in me is offended that my subconscious proposes a version of her that doesn’t care when I’m bleeding out or when I warn of imminent danger. Do I secretly think of mom that way? I wonder after waking. Do I actually think she’s mean? I know that I don’t. My relationship with my mom is wonderfully uncomplicated. We love each other with ease, the way mothers and daughters love each other in stories. But why, then, the cruel mother of my dreams?

Sometimes, when we walk to the library together or on a long car ride, I almost tell her about these dreams. She knows that I have nightmares and intrusive thoughts, and I tell her about some of them. Still, I always spare her the nightmares in which she is cruel. Logically, I think she would understand. But just as I question whether I secretly hate her despite my knowledge of the answer, I worry that she would question her treatment of me or my perception of her. “All moms worry about their kids,” she’s often told me. No need, I figure, to add anything to that burden.

~

In the most vivid nightmare I’ve ever had, my mom had cancer. I don’t remember what kind, but it was killing her. The only part of it I can now recall is its end, when I sat on my parents’ bed, a single lamp in the corner of their bedroom warding off the encroaching dark. My mom wore a thin blue-green shirt, the one she sometimes wears to bed in the summer. It hung loose around her collarbone, where her skin draped her clavicle like sloughing candle wax. I was crying and kneading her knuckles in my hands. All I remember her saying is “I have to go now.” My dad stepped forward and cupped a hand over my shoulder, perhaps in comfort, perhaps to steer me from the room.

I have dreamt of a doppelgänger separating herself from my flesh and turning to strangle me. In my nightmares, I have been trapped in malign labyrinths and caught in active shooter situations at school, at the grocery store, in museums. I was menaced by a murderous clown for months. This vignette at the end of my mom’s bed, her telling me with a rueful smile that the cancer is going to win, has by far been the worst nightmare I have had.

When I awoke, I stared at my ceiling, trying to parse dream from reality, keeping still as though any movement might cross the two threads, might weave the reality of my dreaming world into my waking one. For twenty seconds I couldn’t be sure whether my mom was alive or not. Everything felt too real to be imitation: the texture of her shirt, the way the lamplight folded against the slanted ceiling. Someone shuffled downstairs. I heard the drag of her slippers, the quick gait too light to be Dad, not as deliberate as my sister’s or brother’s.

She smiled as I approached the kitchen, then frowned when she saw my expression. “What’s wrong?” she murmured after returning the half and half to the fridge.

“I had a dream you died,” I whispered, unable to meet her eyes, worried she wouldn’t understand. My fingers twisted at my sides. I was nineteen—too old, I thought, to be so shaken by a dream.

She understood, though. “Oh, Jane,” she said, folding me in her arms, her breath in my ear, warm and easy, her skin whole and healthy.

“It was so real,” I said. If we hadn’t been hugging, I doubt she would have been able to hear it.

“I’m okay, honey,” she said, rubbing small circles into my back. “I’m right here.”

Even though she was standing before me and speaking to me and smiling, the dream was too strong to dismiss, the memory of it heavy enough to bruise. I biked to work and laughed with my coworkers, careful to smile at customers and control my expression even when I thought no one was looking at me. Staring out the window as I assembled salads and sandwiches, I thought of the frail mother in my dream, the way her knuckles shone white beneath thin skin. Her death in my dream demanded to be recognized as reality, competing against the memory of my mom assuring me she was fine at breakfast. As I left for work, I told her that it was just a dream and I would be able to put it behind me, but I still worried as I took orders and made drinks. I felt like an infant, my object permanence nonexistent. My mom vanished whenever I wasn’t looking at her.

During our lunch hour, I turned to take a customer’s order and looked up to see my mom. She was in her gardening clothes, smiling and laughing as my friend and coworker introduced himself to her.

“Thought I’d stop by for lunch,” she told me when I took my place behind the register. “How’s the chicken salad?” I had to remind myself that I was at work, that it had just been a nightmare, to keep myself from crying out of relief.

As she ate, my gaze continually drifted to her, checking to ensure she was still there. She always was. I was taking an order when she stood to leave, but she waited until she could catch my eye and wave goodbye before leaving, a new parting to take the place of the one in my dream.